Researchers at UC Santa Barbara have created a display that turns light into something people can feel. Using tiny pixels that puff up when illuminated, the screen can show moving images that are visible and tactile at the same time. A scanning laser both powers and controls the surface, so no electronics sit inside the display itself. Early tests show users can easily sense shapes and motion, pointing toward new kinds of touch-enabled screens for cars, devices, and interactive spaces.

Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara have developed a display technology that combines visual graphics with tactile feedback by converting projected light into physically perceptible surface deformations. The display consists of patterned surfaces populated with optotactile pixels that expand outward when illuminated, allowing animated images to be both seen and felt. The work, led by Max Linnander in the RE Touch Lab under mechanical engineering Professor Yon Visell, appeared in Science Robotics.

The project began in late 2021 when Visell posed a conceptual challenge: whether the same light that forms an image could also generate a tactile sensation. At the outset, the feasibility of such a system remained uncertain. The research team spent months developing a theoretical framework and running simulations to evaluate whether optical energy could reliably drive mechanical motion at the scale required for tactile perception. Early prototypes failed to produce usable results, and progress remained incremental.

In December 2022, Linnander demonstrated a functioning single-pixel prototype shortly before leaving campus. The device consisted of a single optotactile element activated by brief pulses from a low-power diode laser, without any integrated electronics. When illuminated, the pixel produced a tactile pulse that could be clearly felt by touch. This experiment confirmed that the underlying concept could operate in practice.

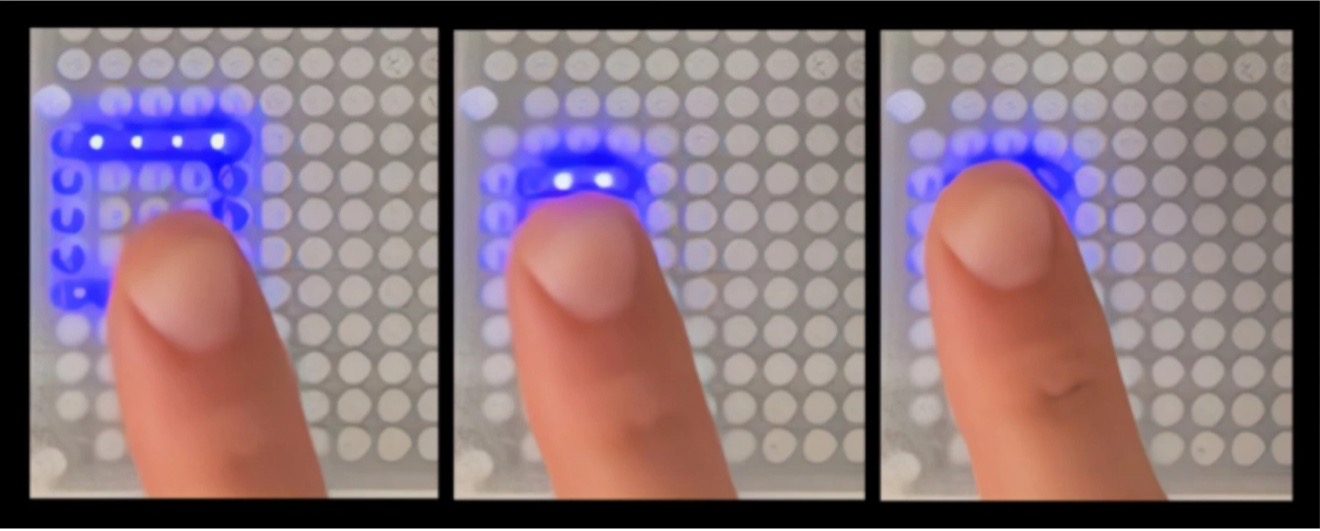

Figure 1. Millimeter-scale pixels lift into bumps when lit up by a focused laser pulse. (Source: UCSB Engineering department)

The display architecture relies on thin surfaces incorporating arrays of millimeter-scale optotactile pixels. Each pixel contains an air-filled cavity capped by a suspended graphite film. When projected light strikes the film, the film absorbs the optical energy and heats rapidly. The resulting temperature increase causes the enclosed air to expand, deflecting the top surface outward by up to 1 mm. This displacement produces a localized bump that users can perceive with their fingers.

Optical addressing controls the pixels. A scanning laser sequentially illuminates individual pixels, delivering both energy and addressing signals without embedded wiring or onboard electronics. The speed of this process allows the system to refresh quickly enough to support dynamic visual and tactile animations, including moving contours, shapes, and characters. Users experience these animations as continuous, similar to conventional video displays.

The researchers demonstrated prototypes with more than 1,500 independently addressable pixels, exceeding the resolution of many prior tactile display systems. The design allows further scaling by leveraging existing laser projection technologies, which could support much larger display areas without fundamental changes to the pixel structure.

User studies evaluated how participants perceived the displays through touch. Participants accurately identified the positions of illuminated pixels with millimeter-level precision and reliably detected moving patterns and temporal changes. These results indicate that the system can present complex tactile information rather than simple point stimuli.

The underlying principle of converting modulated light into mechanical motion has historical precedent. Nineteenth-century experiments by Alexander Graham Bell used modulated sunlight to induce sound in air-filled structures. The UCSB system applies related physical principles within a digital display framework, translating optical modulation into controlled surface deformation.

The researchers anticipate applications in environments where tactile feedback enhances interaction. Potential uses include automotive interfaces that replicate physical controls, electronic reading surfaces with tactile illustrations, and architectural installations that combine digital imagery with physical sensation. The work demonstrates a method for coupling visual content with touch through optical actuation, enabling displays in which visual information acquires a tangible dimension.

LIKE WHAT YOU’RE READING? INTRODUCE US TO YOUR FRIENDS AND COLLEAGUES.