Blackwell, the company’s most recent and advanced GPU generation to date, was formally introduced at Nvidia’s GTC in March 2024. It is the driving force behind all its current GPU products, targeting AI applications as well as traditional visual-oriented applications in gaming and professional markets. The first Blackwell GPUs serving the professional graphics markets came earlier this year, in the form of two RTX Pro cards, both paired with 96 GB memory and targeting the top end of the market. The RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Max-Q Workstation Edition is the more conventional SKU, but it’s the other that truly breaks new ground in the market for deskbound workstation GPUs.

Where past top-end cards—including this RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Max-Q—have tended to max out power consumption at around 300 W, the flagship RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Edition specs 600 W. With its commensurate lofty price (in the $8,000 range, retail),this is not a GPU meant for all users, all applications, nor all machines. But if you are the right user, with the workloads that warrant its capabilities, and with a workstation that can meet its requirements, there has never before been a GPU that can do what this can at your desk… not even close.

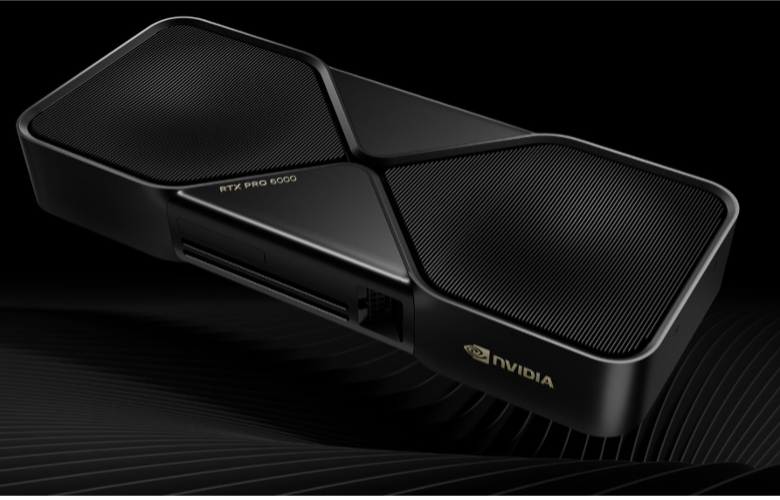

(Source: Nvidia)

First formally introduced at Nvidia’s GTC in March 2024, the company’s most recent and advanced GPU to date, Blackwell, is the driving force behind all its products, targeting today’s market-headlining AI application as well as traditional visual-oriented applications in gaming and professional markets. Fitting the more recent GPU product progression (since Volta), Blackwell’s initial focus and silicon spins succeeded the Hopper generation of AI/compute-focused data center GPUs. Subsequent silicon spins were expected to arrive later, slanted more for visual applications (both professional and gaming). On the professional side, that came earlier this year, with the first RTX—now RTX Pro—add-in card GPU built on Blackwell, a product that breaks norms in more than one way.

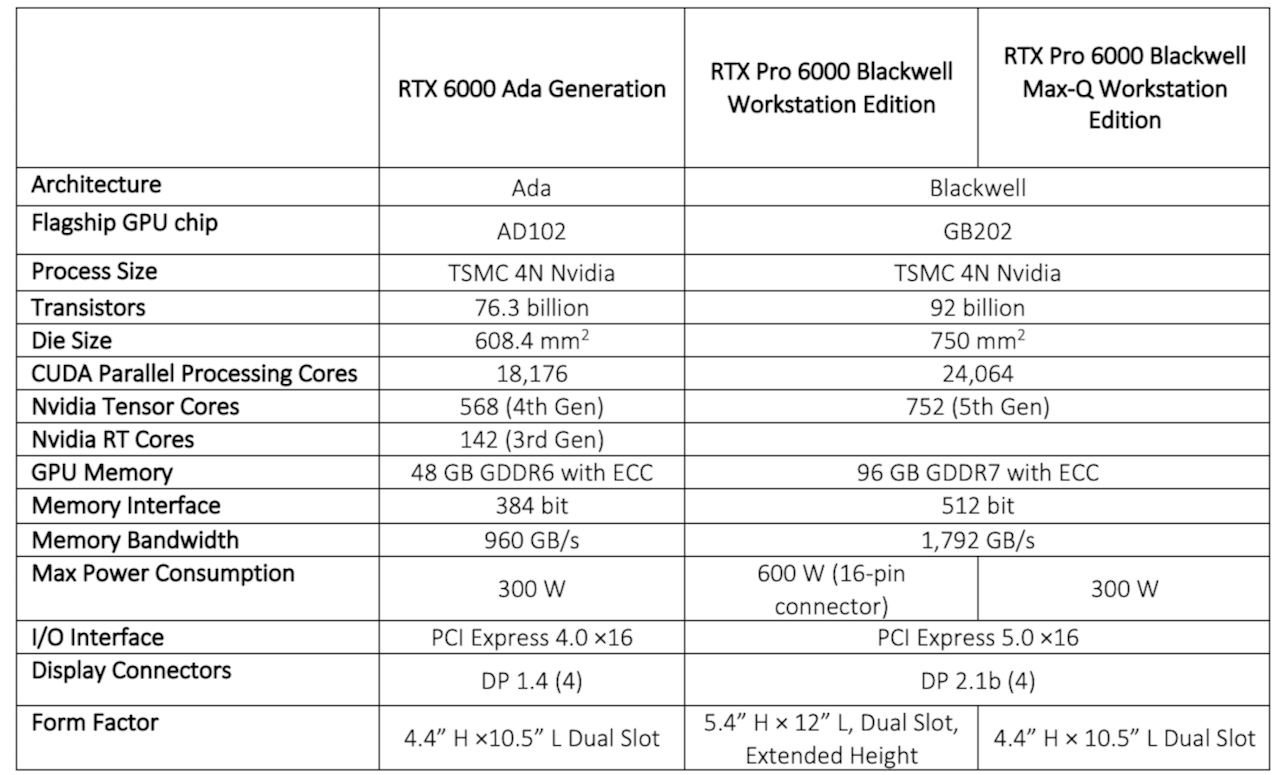

As it had with the prior Ada generation, Nvidia debuted its first professional RTX GPU for workstations based on Blackwell at its top-end 6000 tier, with the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Workstation Edition add-in card. With the bifurcation of application spaces, the Blackwell die in the GB200 was unlikely to become the foundation of traditional RTX GPUs for client use in gaming and professional graphics. Instead, sensibly, the first RTX Pro GPU built on Blackwell is based on a subsequent Blackwell silicon spin, the GB202.

At a modest cost reduction, the GB202 is far from underpowered, allowing the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell add-in card to deliver around a third more computing resources (CUDA Cores, Tensor Cores, and RT Cores). On the professional RTX side comes two versions at that 6000 tier. One is the more conventional RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Max-Q Workstation Edition, cranking up chip resources and doubling GPU memory to 96 GB. The Max-Q version maintains the de facto historical top end in power consumption, at the high but tolerable 300 W. Breaking that de facto limit, however, is the preeminent model, the flagship RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Workstation Edition (i.e., no Max-Q suffix).

Blackwell offers a big step up in computing resources over Ada across the board, but perhaps the most notable line item leaping off the datasheet is the power consumption. Where past top-end cards have tended to max out around 300 W, the flagship RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Edition specs an eye-watering 600 W design power. This card clearly isn’t meant for all applications, nor all machines. Only big, fixed workstations with heavy-duty power supplies and cooling subsystems need apply.

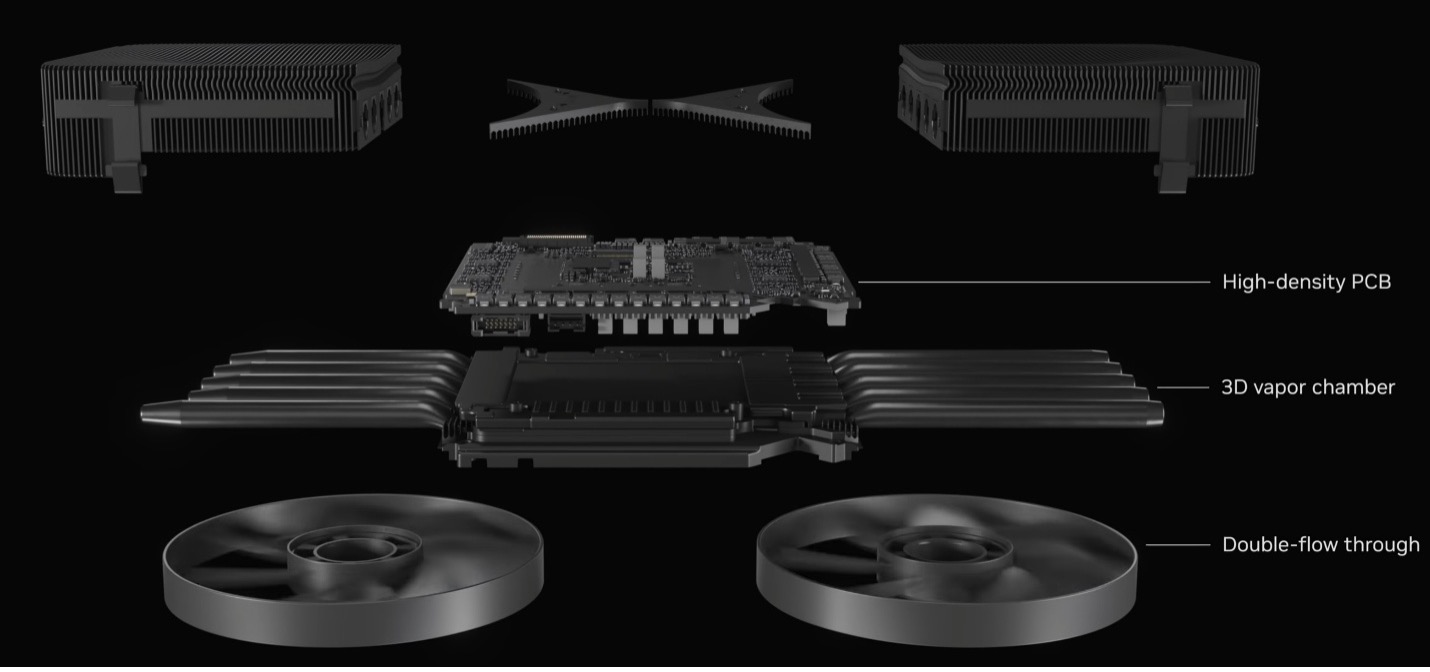

To clarify, “heavy duty” means one capable of supplying 4× 150 W auxiliary GPU (the existing standard 6-pin/8-pin) power cables, which can then be channeled to Nvidia’s more recent auxiliary power connector with a 4× 8-pin pigtail adapter. And to further clarify, “big” isn’t something to be taken lightly but rather literally, as anything but a full-size tower won’t provide adequate clearance. Yes, it’s of similar dual-slot thickness, but the extra height of the card otherwise may not fit within the chassis, let alone provide the additional clearance necessary for that aforementioned power cable, which attaches not in the rear of card as is typical. Rather, this one connects from the top middle of the card, for a reason that one might suspect, but more on that ahead when looking at the card’s internals.

Table 1: Salient hardware metrics for the flagship CPUs behind the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell GPU and its predecessor, the RTX A6000. (Source: Nvidia)

Take a look at the following views of the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell compared to its predecessor, the RTX Pro 6000 Ada. The former is notably thicker, longer, and wider (which translates to its height when inserted into the chassis lot). Suffice to say, unless you specifically know it can, no user should assume this GPU will physically fit. Only true, full-size towers with ample power need apply, and even then the buyer will want to verify the workstation is up to the challenge. Dell’s redesigned Pro Max T2 Tower is one workstation that fits the bill, and likely intentionally designed (at least in part) to handle such a GPU.

Figure 1: The dual-slot, power- hungry 600 W RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Workstation (bottom) dwarfs the hefty-in-its-own-right 300 W dual-slot RTX Pro 6000 Ada (top).

Figure 2: The card’s extra height (which translates to the width visible in the bottom pic above) precludes installation in just any tower, regardless of power supply.

The 600 W RTX 6000 Blackwell is no run-of-the-mill card design

The physical size of the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell is the most obvious sign that this is no card of ordinary power and performance. But simply adding to the dimensions is the least intriguing or challenging aspect of its design. Consider first that engineering a reliable add-in card of the nominal top-end 300 W— think primarily electrical integrity and thermal dissipation—is no trivial feat. Now double the maximum watts, which correspondingly doubles the maximum amp draw, and the electrical and cooling demands enter uncharted territory.

The exploded view below not only shows the attention to cooling with bilateral 3D vapor chambers sandwiched between dual heatsinks and fans, but also why that high-amp auxiliary power feeds the card’s midsection rather than its tail end.

Figure 3: Not just some esoteric nicety but an absolute engineering necessity: the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell’s double-flow through active cooling. (Source: Nvidia)

Dell’s Pro Max T2 tower: an uncommon deskside workstation that’s up to the challenge

Accommodating the size, supplying 600 W, and dissipating the resulting heat are not just engineering challenges for Nvidia but for the workstation OEM as well. Housing the 600 W RTX Pro Blackwell means several issues that warrant extra design attention, if not full-on modifications.

Again, there’s that obvious adjustment to make to the tower dimension, specifically in widening the chassis a touch. At first glance, one might not notice the T2 chassis looking different than any other deskside tower (i.e., not including Small Form Factor or Mini, which are common sizes as well). But it’s the slight increase in the chassis width that’s critical—in this case, measuring 7 3/8” versus, say, 6 3/4” of other high-end towers. That 5/8” might not seem much, but in this case, it’s just enough to let the 600 W RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell’s ample waistline—and extra power connector clearance—fit in the T2, where many other towers wouldn’t comply.

Figure 4: At first glance, Dell’s Pro Max T2 tower doesn’t appear significantly different than any other.

Furthermore, it’s doesn’t take a lot of guesswork to figure out you’ll need a higher-capacity PSU capable of delivering all that power over the 4× 150 W auxiliary cables. In this case, those four cables get merged via Nvidia’s 4-to-1 adapter that’s connected to the RTX Pro 6000’s central, topside interface.

Figure 5: Nvidia’s uncommon 4-to-1 (4×x 150 W) power adapter.

But, as always, the power delivery is only half the battle, and usually the more straightforward half. While Nvidia’s design manages to get the heat moved off the silicon and card, the workstation designers need to ensure they’re getting that heat moved the rest of the way: out of the chassis. That requires both providing the adequate fan capacity and minimizing the turbulence within the airflow that might otherwise choke off that capacity. Fortunately, from the standpoint of thermal engineering, there shouldn’t be a whole lot of difference between cooling down this 600 W GPU (occupying two slots) versus cooling two 300 W cards (occupying four slots), the latter of which has been an existing check mark item for high-end workstation towers for some time.

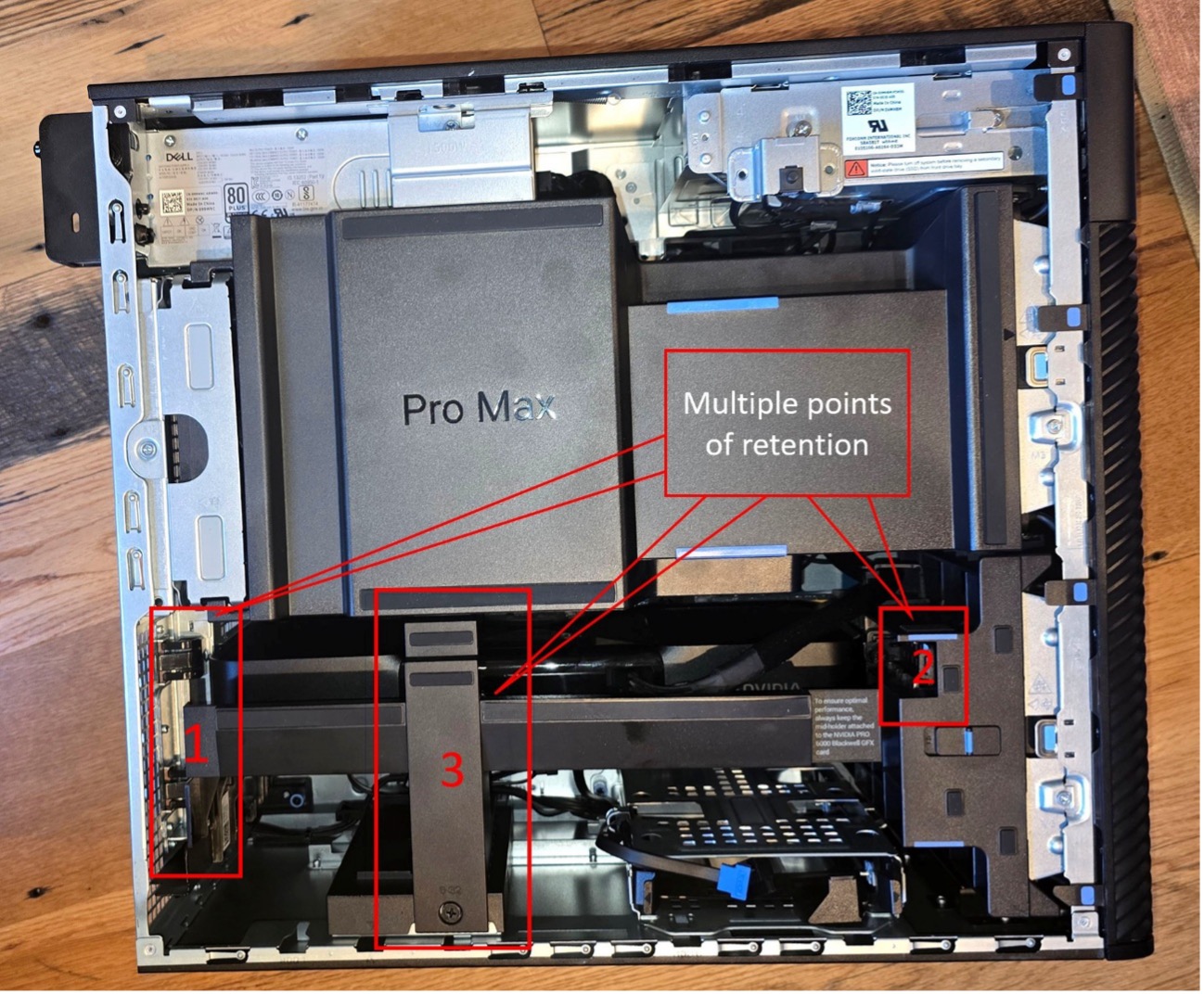

But then there’s the less glaring, albeit not surprising issue that goes along with the bigger physical footprint: weight. Where the RTX Pro 6000 Ada weighs about 2 pounds, 10 ounces—heavy by mainstreams standards but not in the context of top-end cards—the 6000 Blackwell tops out at a monstrous 4 pounds, 3 ounces, around 60% heavier. And remember, we’re talking a workstation here, a machine with the reputation and requirement of absolute maximum reliability. So a wobbly card that might impart excessive stress on the PCI Express connector, or result in a dislodged card, simply cannot be allowed.

A look inside at the structure of the Pro Max T2’s retention points for the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell shows that will not be a risk with this machine. There’s that baseline support from the bulkhead as well as the PCIe fingers and its plastic retention tab, the two often enough for entry to midrange GPU cards. But this card obviously will need a lot more security than that, so Dell fixed a slot on the rear of the chassis for the backend of the card to slide into, with a screw-down tab to ensure it can’t come loose. So far, we’ve got a retention design similar to what has served previous generations of heavier dual-slot GPUs. But nope, that’s still not enough for Dell when it comes to housing this RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell. Putting any concerns about physical stability to rest is an over-the-top, screw-down retention arm (labeled #3 in the image below) that simply won’t allow that card to move the tower positioned in its typically vertical deskside fashion.

Figure 6: More retention points—specifically adding #3—than any other add-in card I’ve seen.

Here, TechWatch subscribers can read about how the 600 W RTX 6000 Blackwell performed when the writer put it through various benchmarks, and how it marks an inflection point in both GPU design and markets.

IF YOU LIKED WHAT YOU READ HERE, DON’T BE STINGY, SHARE IT WITH YOUR FRIENDS.