OpenR2 is a group with the goal of researching and open-sourcing materials for an exact replica of R2-D2, the droid from Star Wars. Robert Jackson has spent approximately 25 years on a quest to bring the robot to life, using his engineering skills to do so. Simply creating an R2-D2 will not do; his version, as is the mission of OpenR2, is to have a replica that is 100% exact to that of the first R2-D2 to appear in a Star Wars movie.

Some people paint, hike, or bike, as a hobby. Robert Jackson’s hobby is more unique. He is building an exact replica of R2-D2, the robotic star that served Padme Amidala, Anakin Skywalker, and Luke Skywalker in a galaxy far, far away. It’s as much of a hobby as an obsession. For him, every detail, every measurement must be exact.

Jackson’s R2-D2 journey began more than two and a half decades ago, when the engineer began working for Silicon Graphics, back in the days when a single machine ranged in price from $45,000 to $100,000. He was hired as the company’s CATIA subject-matter expert, and part of his job as sales/tech support entailed making 3D graphics demos for automotive companies. His boss had a cardboard cutout of R2-D2 in his office—the version that appeared in the first scene of the first movie, Episode IV–A New Hope (1977), which kicked off the now legendary space opera franchise. And thinking he could win favor, Jackson decided to model R2-D2 in CATIA (version 4), using the cutout, a photo, and the movie (on VHS) for reference.

“I didn’t know any of the dimensions. I just knew that the person standing next to him, Mark Hamill (as Luke Skywalker), was about so tall,” Jackson explains.

Jackson obviously made an impression on his boss with that effort—it was part of a project that led to Jackson being named Systems Engineer of the Year at SGI. As Jackson points out, the model had all the correct features, and once he had the numbers from blueprints he had acquired, we just had to modify the values “and everything snapped into place.”

In 1999, as the Internet was taking off, Jackson joined the E2 Builders Club, a community for those constructing their own replica robots from the Star Wars universe. The group numbered about 30 initially but over time swelled significantly. In 2013, Jackson and others broke off and formed the online community OpenR2, an open-source effort whose goals are to research the specifications of the robot prop built at Thorn-EMI Elstree Studios in 1976 and to implement an open-source robotics backbone for those specs using the Robot Operating System (ROS). Over 4,000 members strong, the community has a small core team of contributors comprising those with mechanical engineering skills, like Jackson, and others who perform research/archival tasks or fall on the software side working to make the robot autonomous. As a result of their efforts, Star Wars fans from Earth to the Outer Rim can download original pencil drawings, blueprints, and specifications to make their own droid.

As Jackson notes, there were actually seven different versions of R2-D2 in the film, all slightly different. He and his group are focused solely on the R2-D2 from that first scene in A New Hope, when the droid made its first appearance. “We’re going after the magic of that one you see in the first scene,” says Jackson, who, ironically, does not consider himself a big fan of Star Wars. Rather, he considers himself a big fan of a film where viewers are transported to a whole new world, a totally different environment never seen before, through the use of sets as opposed to dialogue and story. “I really like industrial design, and I’m a very big fan of George Lucas’ industrial design and the whole universe he put together. It was the first time space was portrayed as dirty; all the movies before that were super clean, and everything was silver. Everything had to be made out of real metal, real aluminum in the movie. There’s a lot of mechanical engineering going on in that first film.”

Lucas’ vision was a bit futuristic, and the actual movie design incorporated actors inside the robot shells or were remotely controlled.

It’s worth pointing out that this was the era of pre-digital effects Star Wars; some later models were made using fiberglass or plastic, giving the bot a different look. Today, though, there is a push to return to the original aesthetics in shows like The Mandalorian. And OpenR2 is happy to share their research on that front with the current crop of prop makers.

Built for today… and yesterday

As for Jackson’s replica, “On the exterior, we want it to look exactly like it did in 1976, using the same materials, the same construction methods. On the inside, though, it will be updated to 2023,” he says.

As Jackson explains, the original R2-D2 was designed by John Stears and built at Peteric Engineering, which had been leasing space at Shepperton Studios in London. The company, headed by Dr. David Watling, a former aerospace mechanical engineer who was building custom aluminum sports cars, was asked to build the robots. “The quality of the construction is done like that of a helicopter; it’s just phenomenal,” he says. “The physicality of it holds up. And we wanted to replicate that to a tee.”

This being the 1970s, the electronics from a remote-controlled airplane model were used inside the robot; the motors were from the windshield wipers of a minivan. “So, the electronics were very, very primitive compared to the exterior. That’s why we’re saying that everything on the inside, we are going to replace with current technology. This means using the best motors and Nvidia Jetson. We want it fully autonomous and are using GPU-based embedded systems and machine learning. When you put this Jetson inside R2-D2, it becomes a real robot.”

Jackson maintains that the commercial side of the project, r2Maker, abides by copyright and intellectual property laws and does not sell replicas. The build he is making is for his own use. The documentation from all the information gathered over the years is part of a community project and is available through open source via OpenR2.

However, he does sell parts. Parts of what, you might wonder. The real R2-D2 was not all uniquely fabricated; some parts were, well, actually parts picked up here and there. For instance, R2-D2 has three “eyeballs” around its head. They are not Lucasfilm IP, but instead are part of a reading lamp from an old 1960s British aircraft. Because companies that made parts like these have not been in business for quite some time, r2Maker has taken on the task, making replicas of these various parts by 3D printing them.

On-site, there are three Formlabs resin printers, which are used strictly for validating the prototypes. When making the actual parts, which are made from stamped aluminum, they are machined.

went out of business years ago, but now are 3D-printed and offered by r2Maker. (Source: Robert Jackson and r2Maker)

Jackson holds up a 3D-printed aluminum part, an exact copy of that lamp piece. It is one of the parts that will be offered on r2Make’s Square store, which is set to go live today. There is also a corkscrew part from an old futuristic-looking record player, as well, that had been used for the film model. Those two parts were printed by Shapeways. “If people want it to be the exact materials and the exact paint and the exact dimensions of the original, they can buy those from us,” Jackson says. Builders can opt to machine the parts or 3D print them themselves, since the plans for those parts, like everything used in the R2-D2 model, are available for download at no cost. Advice is also provided for free.

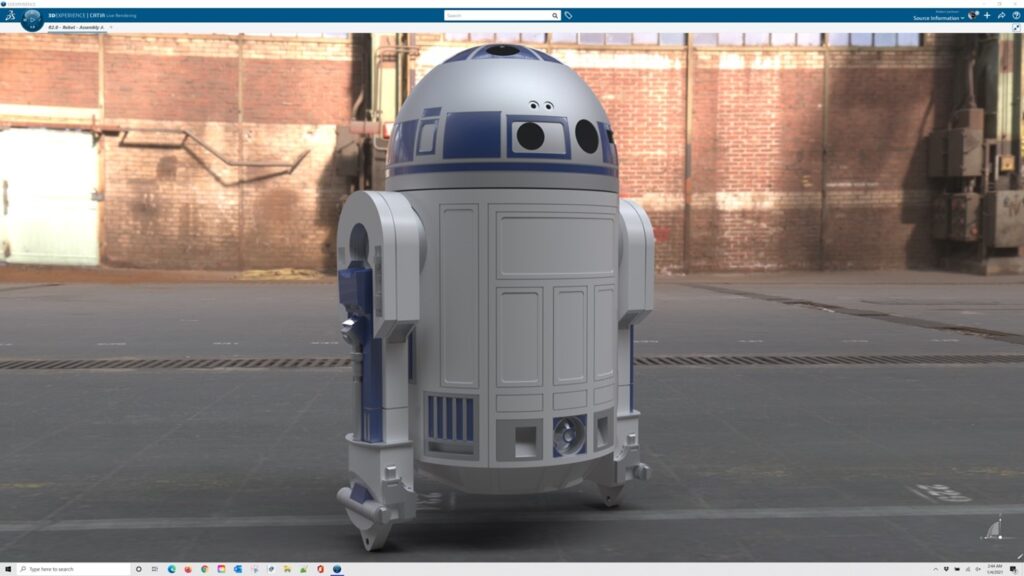

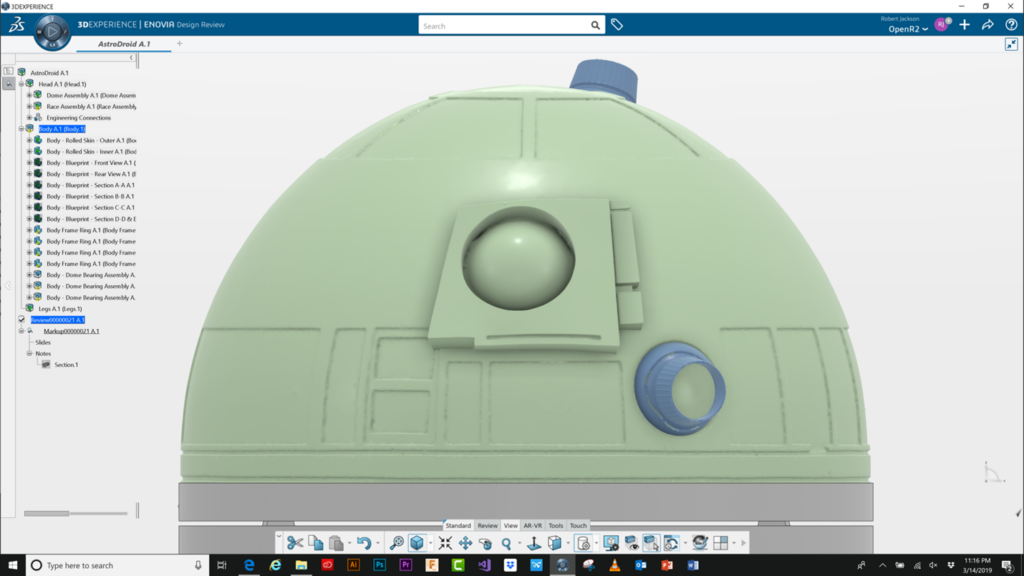

Jackson maintains all the plans and information using 3DExperience in CATIA (version 6). Dassault’s Enovia, powered by the 3DExperience platform, is used for product data management, PLM, change management, and so forth. Jackson has used CATIA for years and continues to do so to this day.

“Currently, there are two robots in there. But eventually you will be able to go in and search on any scene from the first movie, and it will pull together the parts that make that specific robot from the six versions that are in the film. And you can download that data so you can build it yourself,” he says.

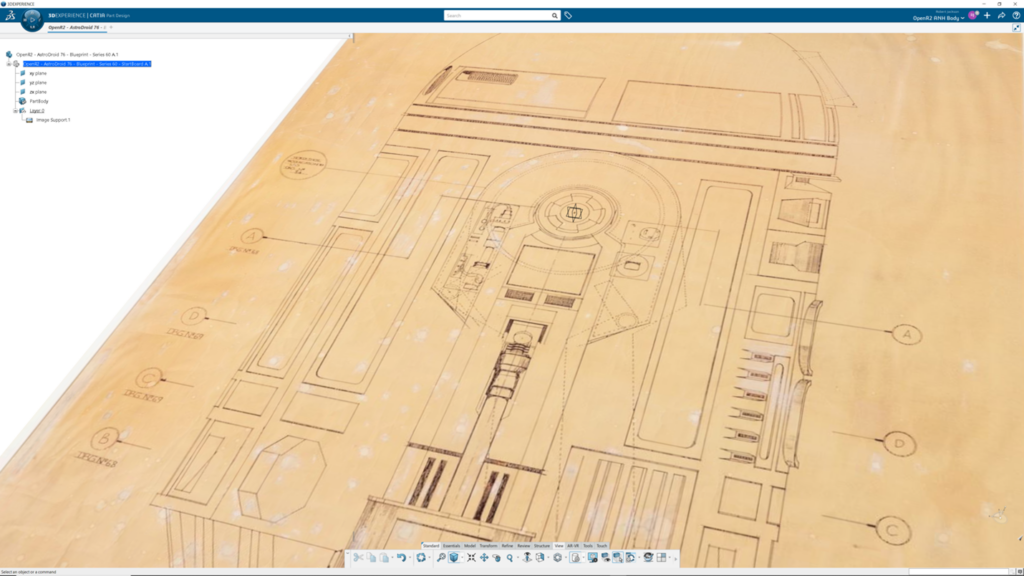

Circling back to those blueprints mentioned earlier: Jackson started collecting R2-D2 data years ago, making a big move when he saw on the internet that a company, which had worked on A New Hope, was selling their copy of the blueprints they had used to build R2-D2. “I thought, is this real? You just don’t see something like this. So I took a chance and borrowed the money from my parents, $4,000.99,” he recalls. As he got older, he began collecting more of these blueprints—some original pencil drawings from the draftsmen, and others the traditional blueprint. He has 10 in all.

“We just do what it takes to win the bids,” Jackson says of the effort. Of course, it does require money, and as a successful mechanical, chemical, and electrical engineer, he no longer has to borrow the money from his parents. In one instance, the contract worker paid $10,000 for a blueprint. Money well spent considering they provide the exact dimensions for the bot.

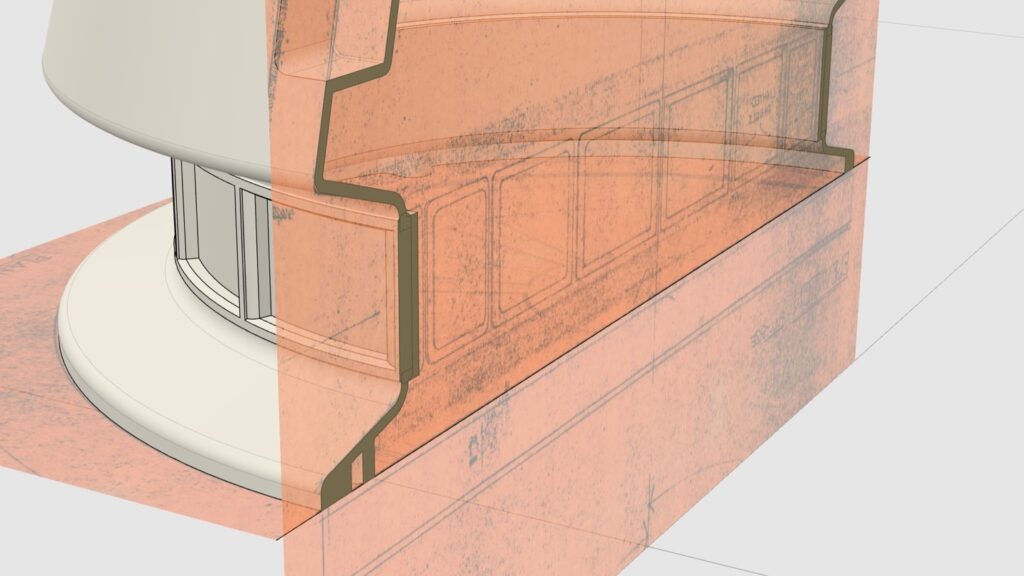

Jackson then scanned those blueprints into CATIA. Almost all of them are fully dimensioned, but there are some that have a really complex shape that had to be traced over. “We would put it into CATIA and either model it based off the numbers or trace over it,” he explains. “A lot of times in film, the blueprint is just a rough guide. But these were mechanical engineers, and they made those robots right to those blueprint specs.”

Mission not quite complete, yet

Four years ago, Jackson set up a five-year goal to complete his R2-D2 builds—he has two in progress. That means he has until the end of the year to have everything done, painted, welded, and assembled. The last year will be all about the robotics.

“Once you start saying, OK, this robot in this scene is this, and that robot in that scene is that, a lot of people’s eyes just glaze over and they say, ‘That’s too complicated. You are going in way too deep.’ But there’s no value in doing it otherwise. What we found was we have this database now and [what we’re building] is different than those R2-D2s people built over the last 10 or 15 years who just eyeballed it,” explains Jackson. “But then Disney released Star Wars in 4K about two years ago on Disney+, and now we all have these big TV screens. So, you can see everything now that had been blurry [on DVD].” As a result, the thousands of so-called replicas out there are not 100% accurate. Does it matter? To some, yes. To others, not really.

To Jackson, it matters. So much so that he has some actual R2-D2 parts from the droid in the film. He holds up a cylinder that was part of the leg from the original prop. He and his group are building up a collection of actual pieces and using them to verify that the blueprints are correct, if for nothing else but to quiet those who contend that prop makers didn’t follow the blueprints to the letter. “Now we can measure the exact pieces and compare them to the blueprint.” There have been some slight discrepancies here and there—but nothing more than stickers that appear on the blueprints but were not placed on the original model.

At this point, Jackson has just finalized and validated the information for his droid. About five months ago, an R2-D2 foot was auctioned off; he did not win the bid, but the company that did is building their own R2-D2, and in an information swap, has provided photos and measurements to Jackson. “We just needed them to verify the measurements, and once that was done, we now have everything we need, so we are actively building him,” he says.

The metal domes are already made. Back at the shop in Tennessee, where Jackson has a farm, the metal bodies are being constructed. “I’m perfectly comfortable with CAD and modeling in 3D. I’m also adept at writing software. What I’m not comfortable with is welding, and aluminum is the hardest to work with,” he says. “My challenge now is I want to have the body welded together and the legs welded together. This summer, it’s going to be all about welding. In the meantime, everything is kind of clamped together at the shop.”

Advances during the last decade in CNC have made it possible to have an online manufacturing company cut pieces and parts from the CATIA files.

As for the brains of the bot, that will involve machine learning and computer vision, with the goal of having the R2-D2 robot able to maneuver safely around a trade show floor at conventions. Jackson will be training the machine learning to recognize stormtroopers so it will release that robotic noise in recognition and follow the stormtroopers. Through machine learning, the bot will be able to map out its environment for the locomotion.

The robot’s operating system, called ROS, is open source developed at Stanford University. In fact, a variant called ROS-Industrial is used in a multitude of manufacturing plants, and recently, NASA announced that they are going to make Space ROS for missions to space and maybe even a distant galaxy far, far away, at some point. That announcement was welcome news to Jackson, as they were four years into their commitment to using ROS; he even took an online class at Columbia University two years prior to learn it.

“Now we can now say our R2-D2 is running the same ROS that NASA is,” Jackson says. And because ROS is open source, all the add-ons NASA produces goes into the open-source community for folks like Jackson and his group to use. He hopes that by the time he gets started in December or January on the robotics portion of his model, NASA will have its first distribution available, and Jackson will start with his R2-D2 running on Space ROS, “because it sounds so cool.”

One of the current challenges is getting a camera inside one of the eyes for the computer vision. Lidar is also needed to map the terrain, which Jackson estimates can be done in about an hour at a convention center, with that data then stored in ROS. Jackson sees the Lidar as the main technology component and will place as many 4K cameras as possible in every nook and cranny where they can be disguised. Meanwhile, processing required for all this will be done by Jetson, a low-powered system for accelerating machine learning applications.

Once the robot is completed, Jackson will take it to various conventions—those geared to Star Wars and those focused on CAD and engineering. He has a partnership with Dassault—they are providing the CATIA and 3DEperience software, cloud storage, and more to aid the community project—and in exchange, OpenR2 will participate at their trade shows with the droid.

“The open project lets anyone build an R2-D2 at home,” Jackson says. “We’re showing them how it was done in the film. But we’re totally open to people downloading the files and 3D printing it, making it out of styrene plastic, fiberglass, aluminum, wood….”

So, how much will it cost someone to build a replica aluminum R2-D2? About $15,000 to $20,000.

While that may sound like a lot of money, Jackson points out that a neighbor of his spent that much for a fishing boat to support his hobby. “This just happens to be mine,” Jackson adds.

For in-depth information on the CAD industry, check out JPR’s CAD report.