Around 1999, early GPUs brought parallel computing to consumers through simple SIMD designs with only a few pipelines, boosting graphics throughput. As shaders grew more complex, strict SIMD struggled with branching and control flow. In 2006, Nvidia reshaped GPU programming with the G80 architecture and SIMT, presenting GPUs as machines that run many lightweight threads. AMD followed with a similar wavefront model, and later, Intel and Chinese vendors adopted related approaches. By blending thread abstractions with SIMD hardware, GPUs evolved into flexible processors for graphics, AI, and scientific computing.

Early graphics processing units that reached the consumer market around 1999 introduced parallelism to a much wider audience than previous vector processors. These early GPUs typically implemented two or four parallel pipelines and executed instructions using a single-instruction, multiple data (SIMD) model. Each instruction operated across multiple data elements in lockstep, which improved throughput for graphics workloads such as rasterization, texturing, and pixel shading. This design represented the first broadly deployed consumer parallel processors and set the stage for later applications beyond graphics.

As GPU programmability increased in the early 2000s, strict SIMD execution exposed limitations. Shader programs introduced conditional branches and more complex control flow. SIMD execution delivered high utilization only when all lanes followed identical control paths. When threads diverged at a branch, the hardware executed one path while masking inactive lanes, then reversed the mask to execute the other path. This divergence preserved correctness but reduced effective throughput, since the processor spent cycles executing instructions for only a subset of lanes. Developers and driver writers needed to structure code carefully to minimize divergence, which complicated programming and limited scalability.

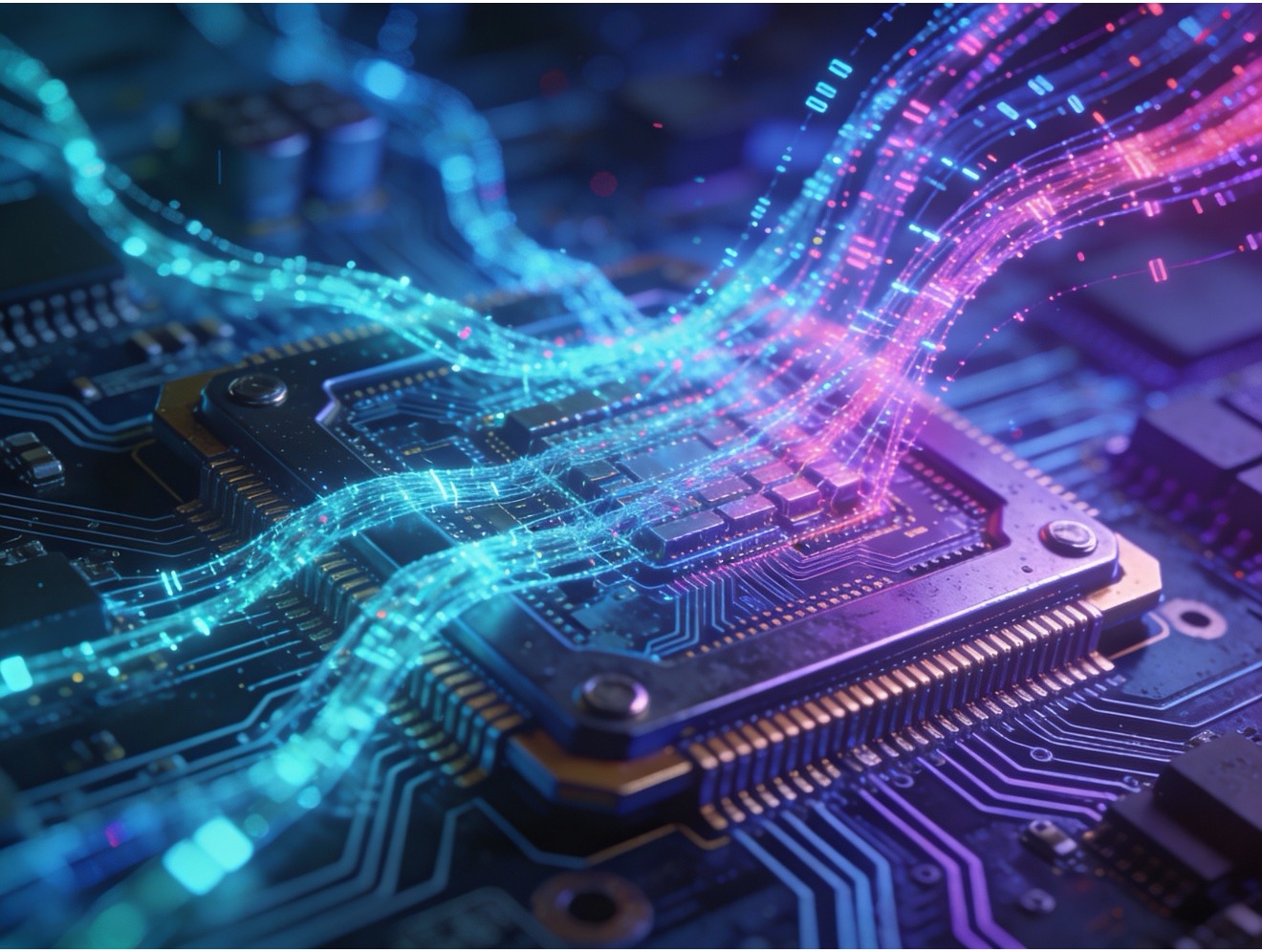

Figure 1. Dataflow diagram of a SIMT architecture. (Source: General-Purpose Graphics Processor Architecture – Chapter 3 – The SIMT Core: Instruction and Register Data Flow (Part 1) | FANnotes)

Nvidia addressed these issues with the introduction of the G80 architecture in November 2006, first shipped in the GeForce 8800 GTX. G80 formalized single-instruction, multiple-thread (SIMT) as the programmer-visible execution model and launched alongside CUDA 1.0. Rather than exposing a fixed-width vector unit, the programming model presented the GPU as a machine that executed many lightweight threads concurrently. Each thread maintained its own instruction pointer and register state, and developers wrote kernels as if each thread executed independently. SIMT can be traced back to early developments in the 1952 ILLIAC IV, Burroughs B6500, and in Flynn’s taxonomy. Flynn’s original papers cite two historic examples of SIMT processors, termed Array Processors.

Figure 2. ILLIAC IV parallel computer’s control unit (CU). In this SIMD parallel computing machine, each board has a fixed program that it would farm out to an array of Burroughs machines. It was the cutting edge in 1966 and ran HAL Beta 0.66. (Source: Wikipedia, Steve Jurvetson from Menlo Park)

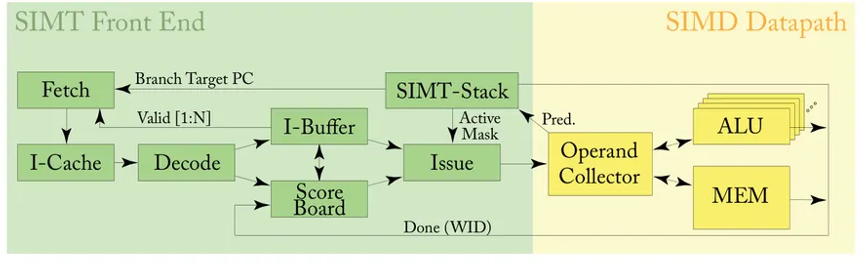

At the hardware level, G80 retained SIMD execution units. The streaming multiprocessors grouped threads into fixed-size bundles called warps, typically containing 32 threads. The hardware issued a single instruction per warp, and the underlying execution lanes processed the instruction in parallel across all active threads. SIMT therefore did not replace SIMD. Instead, it reorganized the abstraction around threads while preserving SIMD efficiency underneath.

Divergence handling distinguished SIMT from earlier programmer-visible SIMD models. When threads within a warp encountered a conditional branch, some threads evaluated the condition as true, while others evaluated it as false. The SIMT execution model handled this by serializing execution of the divergent paths. The hardware executed one branch path while disabling threads that did not take that path, then executed the alternate path with the complementary subset of threads that were active. Each thread progressed through its control flow independently, while the hardware managed masking and serialization. This approach reduced programmer burden and made control-heavy kernels easier to write, even though divergence still reduced throughput at runtime.

Figure 3. A set of SIMT multiprocessors with on-chip shared memory. (Source: Nvidia)

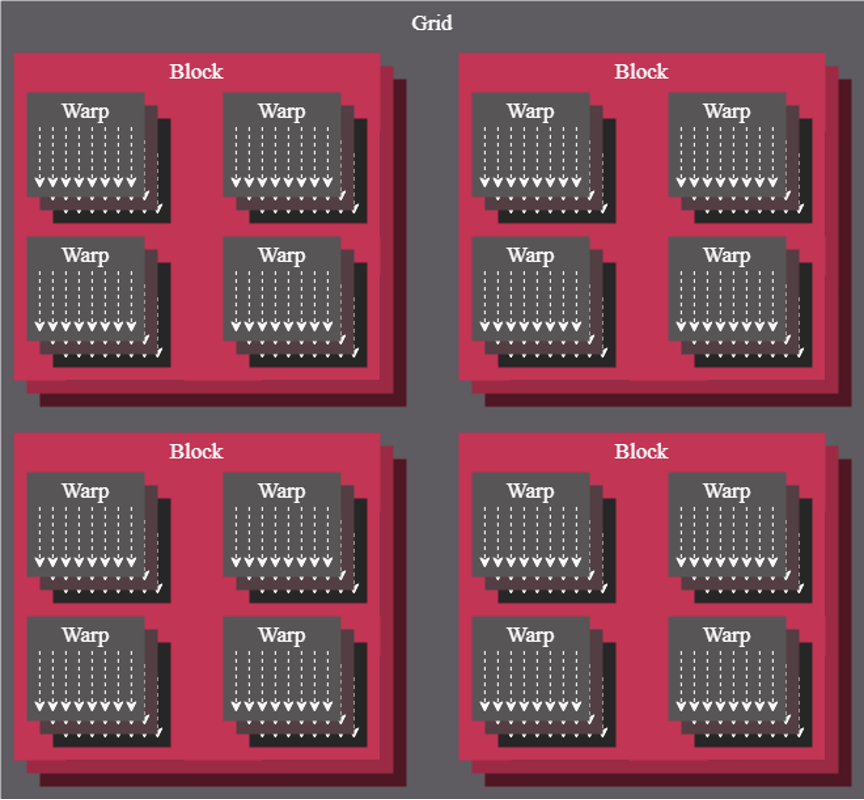

AMD introduced a comparable execution model with the R600 architecture in May 2007, first shipped in the Radeon HD 2900 XT. R600 organized work into wavefronts of 64 threads that executed a shared instruction stream. Each thread maintained its own registers and program state, and divergence triggered a masking mechanism similar in concept to Nvidia’s warp behavior. AMD initially exposed this model through its Close to Metal interface, later formalized through OpenCL and heterogeneous system architecture frameworks. Although AMD did not label the model as SIMT, its behavior aligned closely with Nvidia’s approach: a thread-centric abstraction layered over SIMD execution hardware.

Figure 4. The thread hierarchy inherent to how AMD GPUs operate. (Source: AMD)

Both Nvidia and AMD, therefore, extended SIMD rather than abandoning it. The hardware continued to issue single instructions across multiple execution lanes. The architectural change lay in the programming model and scheduling logic, which treated threads as the fundamental unit of work. This shift enabled GPUs to scale to tens of thousands of concurrent execution contexts while preserving efficiency for data-parallel workloads.

Intel adopted a similar direction much later. In 2021, Intel introduced its Xe-HPC architecture, code-named Ponte Vecchio, which explicitly combined SIMD and SIMT execution units. The design supported hybrid execution modes to accommodate GPU-style workloads alongside traditional vectorized HPC and AI kernels. This approach reflected the convergence of GPU and accelerator design around thread-centric abstractions layered on wide execution units.

Chinese GPU suppliers entered this architectural space more recently. In August 2022, Biren introduced the BR100 and related processors, and explicitly described the design as a SIMT GPU with warp-based execution control. Public materials identified a thread-centric programming model consistent with SIMT principles. Other Chinese GPU developers, including Lisuan, Moore Threads, and MetaX, positioned their products as general-purpose GPUs capable of graphics and AI workloads, but public documentation did not explicitly describe their execution models in SIMT terms. Given modern GPU design constraints, these architectures likely employ SIMD hardware with a higher-level thread abstraction, but vendors have not formally published warp or wavefront semantics.

And the APIs are there

Super hardware is no good without super software to support it. Khronos’ Vulkan’s GLSL and SPIR-V shaders compile down to machine instructions that execute in subgroups using the SIMT model. The API abstracts the underlying hardware SIMT execution while giving developers access to subgroup operations for optimization. Vulkan fully supports SIMT through its subgroup abstraction, which maps directly to the underlying hardware’s warp/wavefront SIMT execution model.

DirectX 12 fully supports SIMT through wave intrinsics, starting with Shader Model 6.0, providing explicit programmer control over parallel thread execution that maps directly to GPU hardware’s SIMT architecture.

And Apple’s Metal API fully supports SIMT execution through its SIMD-group abstraction.

Across vendors and generations, the architectural pattern remains consistent. GPUs evolved from fixed-function SIMD pipelines into programmable, massively parallel processors by introducing a thread abstraction that hid vector width and divergence management from developers. SIMT preserved the throughput advantages of SIMD execution when control flow remained coherent and managed divergence through hardware-controlled serialization when threads followed different paths. This balance enabled GPUs to support workloads that combined arithmetic intensity with nontrivial control structure.

Summary

By formalizing SIMT in 2006, Nvidia established a programming and execution model that influenced subsequent GPU designs across the industry. AMD, Intel, and newer entrants extended similar principles under different naming conventions. The result transformed GPUs from graphics accelerators into general-purpose parallel processors capable of supporting scientific computing, AI inference and training, and a broad range of data-parallel applications.

For additional information and background on SIMT:

Single instruction, multiple threads – Wikipedia

Cornell Virtual Workshop > Understanding GPU Architecture > GPU Characteristics > SIMT and Warps

Basics on NVIDIA GPU Hardware Architecture – HECC Knowledge Base

Warp lanes & SIMT execution – Mojo GPU Puzzles

LIKE WHAT YOU’RE READING? TELL YOUR FRIENDS; WE DO THIS EVERY DAY, ALL DAY.